Pensioners take heed, from an article posted at Financial Advisor Magazine….

—————————————

It’s going to be hard to reverse the damaging effects of ultralow bond yields on the global economy.

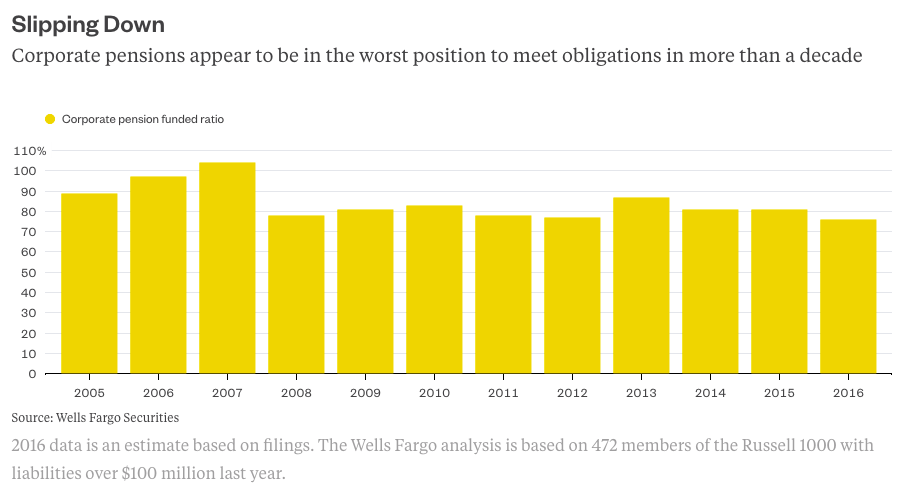

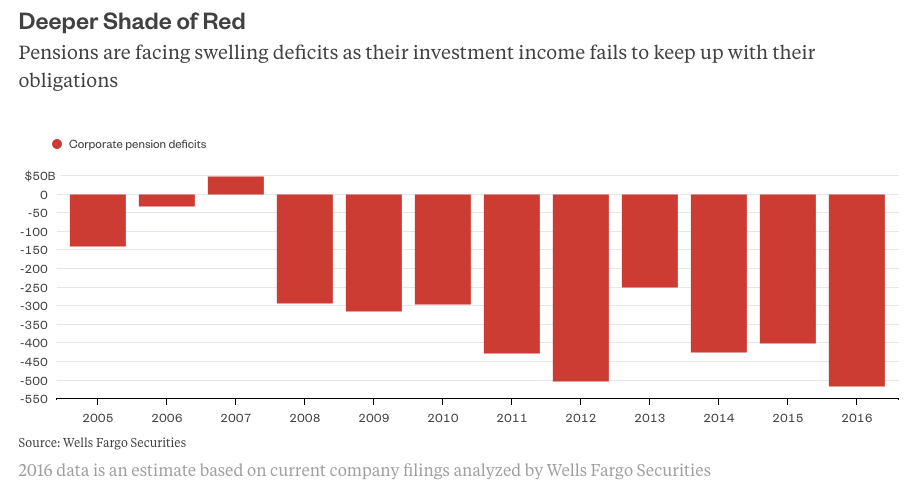

A glaring example of the longer-lasting ramifications can be found by looking at big American corporate pensions, which were formed to provide retirees with a reliable income. These plans are now facing their worst deficit in 15 years, with enough money to cover just 76 percent of their estimated $2.1 trillion of liabilities, Wells Fargo analyst Boris Rjavinski wrote in a Sept. 9 note.

“Corporate pensions overall appear to be in worse shape now than at the peak of the crisis,” he wrote. This is especially galling because companies have poured almost $500 billion into their pensions since 2009, which should have put these funds in a better spot right now.

So why are they facing such a dire outlook? Because they’ve been piling into longer-term bonds to avoid the volatile swings of stocks. Their bond allocations climbed to about 42 percent of their holdings last year, compared with 29 percent eight years earlier, the Wells Fargo analysts wrote.

The problem is that longer-term bond yields have dropped to record lows. These pools of bonds are providing a diminishing amount of income at a time when many pensions still rely on 6.5 percent or higher annual returns. The average yield on U.S. 30-year bonds has fallen to 2.4 percent, about one-half the average over the past 15 years.

Rates on long-term European bonds have fallen to 1.2 percent, about one-fourth of the 15-year average.

In Japan, investors are now paying for the privilege of lending to the government for a decade. Not so long ago, they used to earn money on these bonds. These are meaningful declines, which translate to billions of dollars less for pension funds.

And the problem promises to be long term. Even if benchmark yields start to rise meaningfully, it’ll be challenging for these pensions to benefit because they already have such big pools of the lower-yielding notes. Do they sell their existing holdings and lock in losses? Do they liquidate other positions to buy new bonds? Do they plead for more contributions?

While U.S. corporate pensions are just one slice of the $35.4 trillion global pension industry, they provide a window into challenges that are pervasive throughout the world. Managers of these plans have been choosing between making leveraged bets on companies, nations and properties or accepting a shrinking amount of yield for hanging onto safer debt.

This equation hasn’t been working out too well. The result is that companies and municipalities will ultimately have to contribute more toward these plans or negotiate with their pensioners to reduce their obligations. Both options ultimately lead to similar economic outcomes — they’ll slow the velocity of money and hamper growth.

Companies will be forced to divert money away from developing new products and expanding their businesses. Local governments will have less cash to build new roads, parks and bridges. And retirees will have less money available to spend.

Academics will spend years debating the pros and cons of unconventional monetary policies that led to such low long-term yields. It’s a complicated debate, with legitimate points on both sides. But in this one pocket of the world, there are some deleterious effects that will linger for a long time.